This was the second book on prayer I read, and one which I had a Surprisingly Visceral reaction to. While unpacking that reaction, I realized there was a tension between my expectations of the book vs. what the book actually was—plus how the book ought to be read vs. how it is generally read. So I’m going to break this review down into two parts to make it as fair as possible.

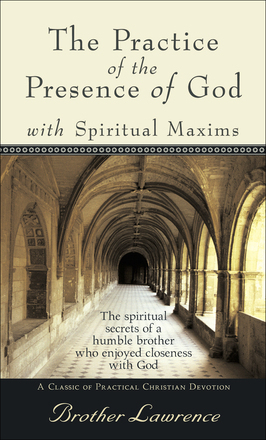

What This Book Is

Brother Lawrence was a lay monk who lived in a Parisian monastery in the 1600s. In his youth, he experienced the brutality of the Thirty Years’ War (both as a civilian and as a soldier), and later he worked as a footman for a French nobleman. By age 28, he had left that job and permanently entered a Carmelite monastery, where he worked as a cook.

The Practice of the Presence of God is a selection of letters and conversations with Brother Lawrence, and the second half of the book includes his Spiritual Maxims. It’s important to realize Brother Lawrence was, by all accounts, a genuinely humble man and probably had no idea these writings would be collected and published posthumously, as they were. The letters and conversations were directed to his listener and really were not composed (as far as I can tell) with any intention of being read as Christian self-help or general spiritual advice. The Spiritual Maxims are a little more ambiguous in nature. Lawrence was indeed known to share his wisdom with others, so it is not impossible he would have sanctioned this collection of his thoughts. That said, Lawrence (much like Kafka) was inclined to “tear [his writing] up at once” (p. 66), so it is hard to discern how he would have felt about publication.

Takeaways and Reservations

The Practice of the Presence of God and Spiritual Maxims contain a very simple theme: Live life ever conscious of God’s presence. There is very little more to it. In fact, Lawrence emphasizes you should not concern yourself too much with worries and thought experiments. Just focus on God being with you, and you will come to know Him.

There were four themes in this book that I found perplexing or troubling.

1) That being constantly focused on and aware of God should be the center of your relationship with Him. This is somewhat too simplistic, to my understanding. Along with prayer, it is essential to read Scripture to know God. That’s not to say Lawrence didn’t study Scripture; it’s just that there are repeated statements such as “his prayer was nothing else but a sense of the presence of God,” etc, which if read naively could be misleading. Also, a lot of the “practice” Lawrence describes has an emotional component to it (by his own words), but remember, prayer need not always be emotional at all.

2) That practicing the presence of God in itself will bring you inner peace and full knowledge of God. I believe Brother Lawrence spoke from his personal experience. I will share that my personal experience has been different…I’ve spent well over a decade practicing awareness of God, nearly moment to moment, and to this day I have not found what Lawrence writes about in this passage (p. 82–83):

…by steadfast gaze on Him, the soul comes to a knowledge of God, full and deep, to an Unclouded Vision: all its life is passed in unceasing acts of love and worship, of contrition and of simple trust, of praise and prayer, and service…

I want to emphasize this is ok. Those reading this book should not feel “discouraged or sorrowful” because of their struggles. It doesn’t mean God isn’t present. I personally believe it’s a very gradual process and that a Christian doesn’t come to that complete knowledge until they meet Christ after death.

3) That suffering should not just be endured but sought as part of our salvation (?). Suffering is another topic I have been studying; in fact, I’m working on an upcoming sequel to my 2018 post on Christian suffering (haven’t decided yet if I’m going to share it here or on my personal blog). I inwardly rebel against quotes like this, not because I think it would be so bad (it wouldn’t) but because I don’t at this point believe it is true:

…those who consider sickness as coming from the hand of God, as the effect of His mercy, and the means which He employs for their salvation—such commonly find in it great sweetness and sensible consolation.

I’ll comment more on this in the post on suffering, where I’ll compare perspectives from a Catholic bishop and an Orthodox priest (one of whom has similar views to Brother Lawrence).

4) That we should live every moment practicing the presence of God, never once letting our mind wander if we can help it. This is going to be a “hot take” so I will try to word it as precisely as I can. The Bible instructs us to pray without ceasing—this I do believe and practice, staying in conversation with God throughout the day. In this book, however, Lawrence talks about consciously focusing his full attention back to God, at every moment, and the way he describes it has characteristics of obsessive-compulsion (I speak from experience here).

Perhaps I am misunderstanding him, but as I read it, I would caution against trying to follow this advice to the letter. My personal approach is to be mindful of God’s omniscience, confident He is fully present and with me regardless of any mental exertion on my part. However, just like any other person I spend the whole day with, I ought to talk to Him throughout the day (and more so). I just see it as being a very natural relationship and not forced by having to redirect my attention all the time.

In Summary…

That was a much longer review than I intended for this very short book. I hope it was helpful on some level. It was not what I expected, but it did provoke plenty of thought. Many people on Instagram let me know it was beneficial to them, so I would say, give it a try—though approach it as a personal testimony rather than a how-to. If you’ve already read it and had some different thoughts or interpretations, let me know in a comment!

Leave a comment