Growing up, I did not learn much about Japanese-American internment, nor was my ignorance remedied by a college history education. Though it took place in local areas—like the state fairgrounds and McNeil Island—it was a topic of WWII that, in my experience, was covered only in passing. Even today, some people shrug it off as a shameful but long-gone incident, or some unfortunate wartime strategy, like the atomic bombings. The idea perhaps is that since reparations occurred, we don’t need to dwell on it anymore. It is one thing to close the case, but without ongoing education on it, we will forget too soon the manipulation, surveillance, and persecution carried out by the US government under FDR, only about 82 years ago.

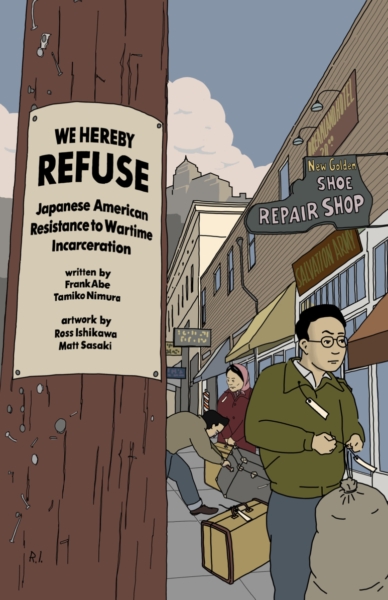

We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration is a 2021 graphic novel following the lives of three real-world figures, including Jim Akutsu who inspired the novel No-No Boy. After Pearl Harbor, more than 120,000 Japanese-American families on the West Coast were forced out of their homes and shipped off to various camps and holding places. In spite of protestations of loyalty and offers to join the military, many young men were held back from serving, falsely categorized as dangerous. Later, when more bodies were needed, the authorities would try to coerce them into a draft. We Hereby Refuse portrays the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) as a collaborator with the government, with some Japanese Americans turning against each other, supposedly to ensure maximum cooperation and good outcomes. Through this chaos, a young woman named Mitsuye Endo chooses to fight her case through the legal system, sacrificing early release in order to uphold her citizenship and that of the other prisoners.

Having previously read No-No Boy and They Called Us Enemy (George Takei’s memoir, also a graphic novel), I am now no stranger to the topic, but this book walked me through details I could not remember encountering before. A blend of narration and bold illustration shows California’s Tule Lake, the largest of the camps, devolve into a dystopian nightmare. Various factions in the camp arise, food is stolen from the prisoners’ rations, and families agonize over how to respond to the government’s loyalty questionnaire in a way that will keep them together. Maddened by the betrayal, some prisoners decide to embrace Japan, horrifying others who want nothing to do with it. A mother is worried sick into depression while her sons are thrown into prison for answering “no” to questions that would implicate them as ever having been loyal to the Japanese emperor. It is a lose-lose situation for the “no-no boys”—the choice is two evils.

The quotations from some of the white politicians and JACL representatives are extremely troubling. Some of the politicians were unabashedly racist, comparing this minority to rats and calling for them to be put in “concentration camps.” I looked up some of these quotations as I went and found the sources for them; the authors of this book seem to have done thorough research. The truth is worse than I thought, if not altogether surprising. A politician would have to be severely paranoid and racist to support such actions in the first place; saying these words is just the first step.

Reminiscent of To Kill a Mockingbird, it is Ms. Endo’s white lawyer, James Purcell, who spearheads the effort to free her and all the interned Japanese Americans. Between the two of them—Endo waiting patiently and nonviolently in the camp, Purcell working on the outside—the case eventually makes its way to the Supreme Court. The Court rules in favor of Endo, and FDR’s administration is forced to recant its policy. Unfortunately, a change in policy cannot undo the trauma that has already been caused, and the book ends on a very dark note.

In terms of a graphic novel, I preferred the art style and typography of Takei’s book. This one is a little too information heavy to be easy to read, and some of the fonts are hard on the eyes even for this nearsighted reader, making it a book I’m unlikely to recommend to visually challenged people. It was also difficult to follow all three narrative strands easily. I got the gist of it, but most of the time I was just floating along trying to take it all in. The art was fine but did not move me in the way that They Called Us Enemy did, with its softer, child’s perspective. We Hereby Refuse would probably have been better told as a prose novel.

Despite the drawbacks of the formatting, this book’s content is still a must-read for those trying to learn about this period of history. I was also glad to see it was produced and published locally in Seattle.

Leave a comment