This review contains spoilers

I remember the first time I finished The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. I was somewhere between 8 and 10 years old, curled up in a mustard-colored barrel chair we had got second hand from somewhere, in the family room when it still had the ugly gray carpet (complete with cigarette burns from a past repairman). I was nowhere near my actual surroundings… mentally, I was in Switzerland and my hero had just died a sudden and, to me, wholly unexpected death. There were very few things that could ruffle me at that age, but my little heart sank. It was the first time I really grieved for someone, fictional or otherwise.

We have a great many beautiful waterfalls in the Pacific Northwest, and I don’t think I’ve looked at one the same way since “The Final Problem,” in which Sherlock Holmes calmly and quietly accepts the revenge that Professor Moriarty has intended for him. The “Napoleon of Crime”—having himself been chased into a trap through Holmes’s tenacity—has nothing left of his old organization except himself, now on the run. Hatred and pride overtake him, and he intends to put an end to Holmes even if it means a duel to the bottom of the Reichenbach Falls.

This story is the last of eleven (in some editions, twelve) stories that make up the Memoirs. That there is no clue to Professor Moriarty in any of the preceding stories hints at the fact that, as my reading buddy Cyberkitten pointed out, Doyle was ready to let go of Holmes for good. From what I understand, he had generally thought of Holmes as “light reading” and maintained a personal preference for his historical fiction and nonfiction works (he was knighted for a book on the Boer War, after all). So, in the vein of a Bond movie but preceding the trope by decades, Doyle put forward the character of Professor Moriarty, evil genius who most certainly was behind many of Holmes’s cases and only revealed to Watson and the reader now.

The other stories in Memoirs, to be sure, stand on their own legs and don’t need Moriarty to give them their macabre. I have always enjoyed “The Stockbroker’s Clerk,” it is such an odd and eerie little story about a job application gone wrong. “The Gloria Scott” appalled me this time, its description of a massacre sinking in in a way that has not previously. “The Naval Treaty,” a surprisingly long story, gives us a bit of off-screen action (delightfully on-screen in the Jeremy Brett adaptation). More than ever, Holmes must use his powers of deduction, his encyclopedic knowledge of crime, and his training in martial arts and fencing to bring crimes to justice.

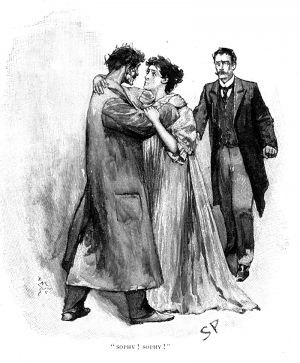

Perhaps my favorite story, apart from the last one, is “The Greek Interpreter.” Again, a vivid childhood memory—reading this at night and getting quite terrified by the Sidney Paget illustrations! While this story is relatively simple from Holmes’s perspective, the creativity and darkness of it have always appealed to me. As in so many instances, Holmes’s presence and care for his client are as important in the story as his actual detective work. It shows a real love for humanity that you don’t find in every mystery series.

That he is very fond of Watson is never more evident than in all the stories, throughout the Memoirs, where he asks Watson to join him on a case, in spite of Watson’s job and marriage. I find it most aptly summarized in this quote however… in a slip of memory, it’s as if Watson never left Baker Street: “They set fire to our rooms last night. No great harm was done.”

In “The Final Problem” we see the pinnacle of Holmes’s altruism. Arguably, it would be in his benefit to let Moriarty and his gang go on indefinitely, never running out of problems to solve. But Holmes shows at last and with action that ridding the world of evils is as important to him as the game itself.

Leave a reply to The Return of Sherlock Holmes – Classics Considered Cancel reply