My first encounter with Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles was in the mid-90s. The children’s public TV show Wishbone aired an episode called “The Slobbery Hound,” of which I remember nothing except the scene with the painting. However, the plucky little Jack Russell terrier helped me fall in love with classic literature, and especially Sherlock Holmes, which I went on to read when I was 9 or 10.

Having since encountered the story in several adaptations—including “The Hounds of Baskerville,” BBC Sherlock‘s sci-fi flavored take on the tale—I went into the reread of the novel with moderate expectations. Out of 4 novels and 56 short stories, it was never a special favorite of mine and once you know the “whodunnit,” there isn’t much of a story left. It’s a slow burn mystery and Holmes isn’t even there for most of it.

I was, therefore, pleasantly surprised how much I enjoyed it this time around. Doyle wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles after an eight-year hiatus from writing the series, and the break shows, in a good way. This takes place some time before “The Final Problem,” and the fact there was no pressure on Doyle to resolve loose threads or continue a deceased character may be why the prose in Hound is so good.

His descriptions of Dartmoor make for fine nature writing in their own right:

The wagonette swung round into a side road, and we curved upward through deep lanes worn by centuries of wheels, high banks on either side, heavy with dripping moss and fleshy hart’s-tongue ferns. Bronzing bracken and mottled bramble gleamed in the light of the sinking sun. Still steadily rising, we passed over a narrow granite bridge and skirted a noisy stream which gushed swiftly down, foaming and roaring amid the grey boulders. Both road and stream wound up through a valley dense with scrub oak and fir. At every turn Baskerville gave an exclamation of delight, looking eagerly about him and asking countless questions. To his eyes all seemed beautiful, but to me a tinge of melancholy lay upon the countryside, which bore so clearly the mark of the waning year. Yellow leaves carpeted the lanes and fluttered down upon us as we passed. The rattle of our wheels died away as we drove through drifts of rotting vegetation—sad gifts, as it seemed to me, for Nature to throw before the carriage of the returning heir of the Baskervilles.

Having read many other Doyle novels where he romanticizes places outside of England, it’s especially interesting he chose the moor for the setting. It makes me realize that perhaps many of his English readers had not visited it personally.

It’s not only in the nature writing that he shines, but in the characters. In other stories in this series, the supporting cast often defaults to open-mouthed incredulity at Holmes’s brilliance, exaggerated in such film caricatures as Nigel Bruce’s Watson (a lovable Watson, to be sure, but not the brightest bulb). But here in Hound, we have a number of clever individuals that aren’t Holmes.

Dr Mortimer, a man of science, first brings the case of the Baskervilles to Holmes at Baker Street. He is concerned about the fate of young Sir Henry, the next-in-line who is about to arrive at the estate after his uncle’s tragic and grotesque death. Dr Mortimer’s astuteness puts the investigation off to a good start, not always the case with Holmes’s clients. The case is further shepherded by Watson, who is sent by Holmes to do a preliminary investigation.

Watson in this novel is quite active and conscientious, finding ways to interview and observe different people in the locale of Baskerville Hall. There aren’t many, but each have their own agenda. Stapleton is a butterfly hunter who lives with his sister at Merripit House. Mr Frankland is a cantankerous old man who has worked out all the intricacies of “manorial and communal rights” and lives for suing his neighbors. The Barrymores, who take care of the Hall, are clearly scheming something behind Sir Henry’s back. There is nobody in the novel too dim to plan a murder.

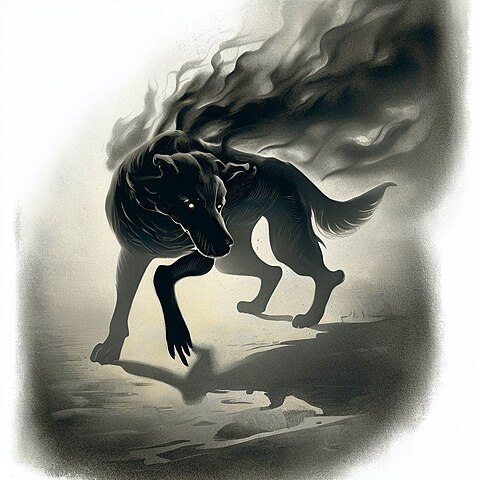

I thought I remembered the story thoroughly, but there were certain details I’d forgotten. I became quite engrossed towards the end, especially when Holmes came back on the scene. Even early in the book, I had a nightmare about the Hound, which was unsettling—I don’t often dream about books I read!

As for the mystery, I found myself chuckling a bit as I turned the last pages. It’s not as well crafted, in my humble opinion, as The Sign of Four. Besides being quite a slow burn instead of a constant thriller, there are one or two loose threads that even Holmes shrugs his shoulders at. I also felt like even the concrete explanations were exceedingly far fetched.

Nonetheless, The Hound of the Baskervilles is iconic for a reason. Doyle created a Gothic mystery that is almost entirely British in location and characters, which, if you recall his tendencies to globe-trot in his stories, is quite a feat. There is not a single mention of the deerstalker cap in this story, yet thanks to the (delightful) Basil Rathbone adaptation, we can hardly picture Holmes out on the moor without it. The Hound of the Baskervilles serves as an anchor in the series, both as the middle story and also in how it cements Holmes as a figure who exists outside the confines of his timeline.

Leave a reply to Marian Cancel reply