My main exposure to Sleepy Hollow has been through the Disney animation, a yearly viewing tradition in my family. Bing Crosby—my favorite old-time crooner and Washingtonian celebrity—narrates and sings the whimsical musical version of Washington Irving’s stately tale. In it, the hapless schoolmaster Ichabod Crane is thwarted in love and money by his archrival Brom Bones, whose ingenuity preys upon Crane’s superstitions about the ghostly apparitions around their sleepy Dutch-American town.

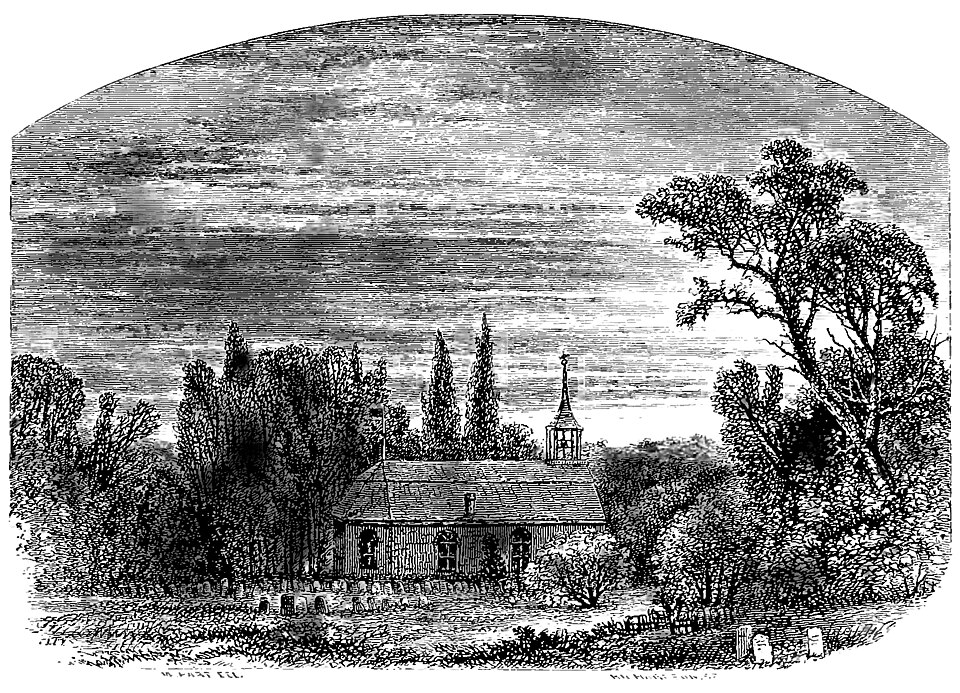

This year, I have not yet watched the film, but I reread the original short story for a group readalong. I found a delightful version on Wikisource that has wood engravings from the 1860s reprint and settled in.

One thing the Disney version does very well is build up tension and… well, spookiness. There seems to be a real and imminent threat to poor Ichabod, lurking in the smiling town and in the monstrous forest. By contrast, Irving is content to meander through Sleepy Hollow, stopping frequently to comment wryly upon the nature of its inhabitants or describe the beautiful autumn scenery. Even when Ichabod is confronted with his worst nightmare, the climax of the story is unassuming and the apparition most mild-mannered—not like the vicious being in the animated film.

What I most appreciated in the short story were the historical asides. Ichabod Crane’s fears are largely rooted in overconsumption of a book of witches by Cotton Mather, and the Headless Horseman is fabled to be a Hessian mercenary from the American Revolution. These details point to a larger, American literary tradition—the ghost of history horrors past—one which would be furthered developed in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s preoccupation with the Salem Witch Trials and William Faulkner’s exploration of Southern Gothic decay.

The other interesting tidbit about this story was how it influenced American literature as a whole. According to what I read on Wikipedia, Washington Irving was in need of cash and prevailed upon Sir Walter Scott to help him get a book of short stories published in England. This became The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1819–20) and included another one of his famous stories, “Rip Van Winkle.” The British reading public was impressed with Irving’s use of language, and it gave credence to American literature at a time when it was looked down upon by some English critics.

I must say that while I was not much frightened by “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” I very much enjoyed its descriptions of the New York countryside and traditional foods that the thin but ravenous Ichabod Crane was such a glutton for. As a West Coaster, I have not been to New England in 15 years, and it might as well be a different country to where I grew up in the Northwest. Still, there is something about New England literature—in all of its loquaciousness, historical pondering, and Puritan-religious underpinnings—that I connect with strongly and feel to be part of our shared American heritage. In this very tongue-in-cheek story, we get just glimmerings of the Horseman, but a very vivid picture of early American industry, values, and traditions.

Leave a reply to Cyberkitten Cancel reply