This book review includes some religious reflection. Please feel free to skip if this isn’t your cup of tea. 💛

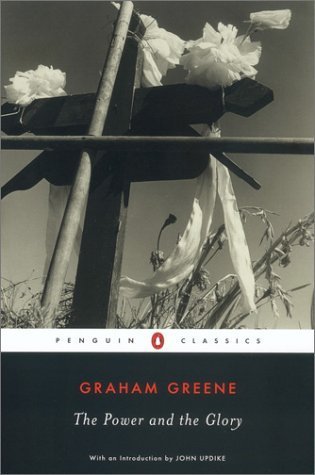

Back in July, some friends and I arranged a readalong for September. By the time this month rolled around, I was in a bit of a pinch, having already set aside Light in August and begun burrowing through East of Eden. I picked up Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory expecting another interesting and challenging read, yet wondering if I’d possibly manage to finish it…

This little novel lost no time in taking me by surprise. What started out as a reading interlude has become a highlight of the year.

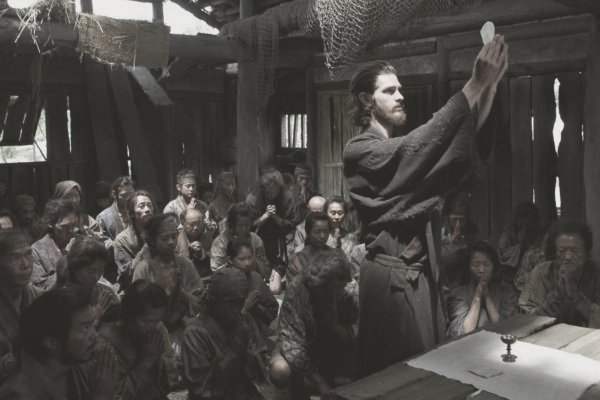

Persecuted Priests – From Japan to Mexico

The Power and the Glory drops the reader in an unlikely dentist’s office, the scene emerging with Conradian unease. It is 1930s Mexico, and an ambitious young Red Shirt in the state of Tabasco is on the hunt for the last priest, who is caught between two snares. To capitulate to a forced marriage would be betrayal, while celebrating Mass openly is to sign his own death warrant. The priest, moreover, is in need of confession; his secret sin weighs heavier than his years of hiding. What keeps him wandering across Tabasco is his duty of bringing the Eucharist to the faithful—but has he embraced suffering for the right reasons?

One naturally compares this story with Silence, Shūsaku Endō’s novel of the persecution of Japanese Catholics. Two books could not be more alike and yet more different. Both are set in periods where Christianity, once welcomed, is now banned. Both have their Judas characters, almost note-for-note mirrors of each other. Yet Endō’s prose is relentlessly grim, while Greene’s scintillates with wry humor and endearing characters, like fireworks in a dark night. In Silence, the priest is distressed by the seemingly infertile ground of Japan; in The Power and the Glory, the priest is terrorized by his own guilt. Endō’s protagonist doubts God for His lack of intervention. Greene’s antihero never stops believing in God or sin, both growing only clearer to him through his experiences.

Greene’s lively prose in no way detracts from the enormous weight of his novel, which is anchored in Roman Catholicism. The necessity of regular confession and Communion, the sacredness of the priesthood, and the doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist are all essential to the plot. Readers must recognize these as matters of spiritual life-and-death to the protagonist. On points where my theology did not align, I could at least empathize.

Our Father’s Image

There are endless threads, characters, and plot twists to analyze in this novel, but what lingers most in my mind—and what has given me a new thought to think—is what Greene writes of imago Dei. Christians believe all humanity, whether believers or not, have something in common from God: something we have been gifted since Creation. In some way or ways, not precisely defined, we resemble God. And this is referenced at least twice in this novel.

In one scene, the priest listens to a devout woman who is scolding him for what she perceives as his failure:

He couldn’t see her in the darkness, but there were plenty of faces he could remember from the old days which fitted the voice. When you visualized a man or woman carefully, you could always begin to feel pity—that was a quality God’s image carried with it. When you saw the lines at the corners of the eyes, the shape of the mouth, how the hair grew, it was impossible to hate. Hate was just a failure of imagination. He began to feel an overwhelming responsibility for this pious woman. ‘You and Father José,’ she said. ‘It’s people like you who make people mock—at real religion.’

Once he sees God’s likeness in others, the priest’s heart opens to their humanity, however contrary or detached it might be from his own. He begins to listen humbly to the voices in the world around him, a far cry from the fêted luxury of his former life.

In another scene, vandalism blights a graveyard:

The wall of the burial-ground had fallen in: one or two crosses had been smashed by enthusiasts: an angel had lost one of its stone wings, and what gravestones were left undamaged leant at an acute angle in the long marshy grass. One image of the Mother of God had lost ears and arms and stood like a pagan Venus over the grave of some rich forgotten timber merchant. It was odd—this fury to deface, because, of course, you could never deface enough. If God had been like a toad, you could have rid the globe of toads, but when God was like yourself, it was no good being content with stone figures—you had to kill yourself among the graves.

The last sentence stunned me, not only for its crude imagery but for the significance it attributes to imago Dei. Can violence against religious statues—and against human beings, and against self—be really a proxy war against God? When we hate another person or ourselves, is it in some ways a hatred of the Creator whom we resemble? In contemplating this strange paragraph, I felt a little bit closer towards understanding, if still on the periphery. Perhaps the image of God can only be defined by analogy, similar to Aquinas’s use of analogy in describing God Himself.

In its visceral frankness, this graveyard passage sums up one of the great themes of this novel. Of course, there are all kinds of earthly reasons that people hate each other, wars happen, and people die. The economic and ideological motives are not absent here. The young soldier is an understandable antagonist—a man of noble intentions behind his cruelty. But underneath the material motives are what the Christian sees as spiritual battles: image-bearers at war. What might be the key to understanding violence in the world may also help us to see the Image in our enemies, and be able to love them as Christ told us to.

There is so much more to write about this novel, many facets that could be essays of their own. I’ll stop there for now, in hopes that these omissions will inspire you to pick it up. It is a heavy story, but if you ever find yourself in the right headspace for it, I highly recommend it.

Leave a reply to Marian Cancel reply