Recently my beloved was in town, and we got to watch a few films together, including Silence (2016). This is the acclaimed adaptation of the novel by Shusaku Endo, which I read and reviewed during the pandemic.

Most of you will recall I was really invested in Endo’s writing a few years ago. I read Sachiko, The Golden Country, and “Unzen,”—three different expressions of Endo’s grappling with his faith and the history of Catholicism in Japan. I picked up The Samurai (1980) last year, which covers similar themes but from a different angle. I set aside the book because I wasn’t in the right headspace for it, only to try it again now after watching Silence.

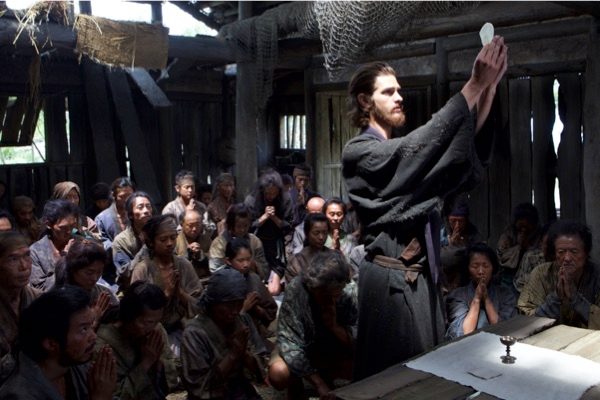

Silence follows two young priests who travel to Japan in search of a lost cleric, Father Ferreira. They seek to dispel the horrifying rumor that Ferreira apostatized after extreme torture in the hands of the authorities. With a shifty guide named Kichijirō, Rodrigues and Francisco try to minister to the faithful they meet along the way. They must also avoid the swift retribution of the Inquisitor, a powerful official who is determined to stamp out Christianity and the influence of foreign powers.

I had previously been uneasy about watching a film I was sure would be violent. And to be sure, there is some violence. But there is nothing gratuitous about the portrayal of persecution. It is well paced and selectively brutal, only shocking the viewer enough to get its point across and no further.

Silence is actually a very beautiful film. The Japan it shows is bleak and mysterious, alluring and inspiring. The berobed priests meet berobed Japanese dignitaries, and the 21st-century viewer sees more similarities than differences. If it weren’t for the atrocities the story is about, you might almost want to travel back in time and experience this strange old world and its clash of cultures.

In such a well-crafted film, the actual dialogue was a bit of a letdown. The lines were fine, but the delivery of lines was rather hammy in places. I wish there had been a bit more subtlety, as well as nuance in how the villagers were portrayed. It just strayed too often into the errors of old films, where people in other countries are portrayed in an overly simplistic way.

Other than that, I was impressed by Silence as an adaptation. I wondered if it maintains enough of the ambiguity of the novel. I do think it is plenty ambiguous. It also made me cry. We talked about the many temptations that Rodrigues encounters in the movie and how, for the Christian, the only way to discern truth from the voices in your head is to go back to Scripture. I felt that a righteous anger (not to mention the guidance of the Holy Spirit) would have spared Rodrigues from many griefs, but wondered too if his faith was sincere…

The Samurai is about a (surprise) a samurai who is deployed on a mission to Mexico to negotiate trade with the Spanish. Whereas Silence is primarily a religious novel, The Samurai is—at least in its first 50 pages—more of a political drama. Velasco is a priest with questionable motives, something of an Endo archetype. But the samurai Rokuemon is a very sympathetic character, one who would prefer not to leave his wife and children for unknown lands and for an unknown period of time.

The sadness of this man is greatly touching and applies a much-needed human lens to these lofty historical events. One senses that something very bad is going to happen to Rokuemon, but in a sense, it has already happened. He is a samurai, but he does not have complete autonomy over his life. Endo reminds the reader gently that people “at all times and in all places” have deep feelings and emotions about their situations, even if their situations are normal for their time period. The humanity of Rokuemon is more powerful than the pride of Velasco.

There is much ugliness in Christian history, especially when it has been strongly linked with political scheming. Endo’s exploration of Christianity in Japan, from the 17th century to the 20th century, makes you question the motives and actions of East and West alike, as both had, at different times, played the monster.

What you do find in these stories, however, is the enduring presence of a faithful few, a “remnant” as the New Testament puts it. These saints do not seek power on earth, but instead, a humility rewarded in the Kingdom of Heaven.

Leave a reply to Cyberkitten Cancel reply