While on vacation last week, we stopped by some marvelous bookshops, and Mr H treated me to some new books of my choosing, one being a collection of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poems.

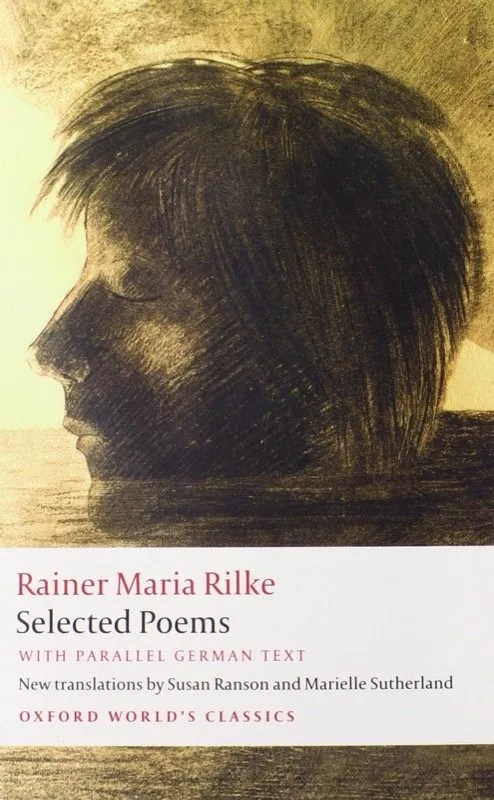

Rilke—a contemporary and fellow countryman of Franz Kafka—had crossed my radar ages ago. Like many other misfortunates, he was quickly buried under my ever-growing TBR list, not forgotten but a dim memory. It was an Instagram post that pulled me back to him recently with “The Swan,” an oddly optimistic and uplifting poem about death. From there, a fortuitous glance through his Selected Poems (Oxford World Classics) led me to lines that seemed to speak into the crisis born in my own time and heavy on my heart this year.

The emperors of earth are old

and have no heirs. Their sons died young,

and their pallid daughters loosed their hold

on the crowns bequeathed them and yielded into

the hands of force the sickened gold.

In this Susan Ranson translation, Rilke goes on to describe a some mysterious entity, “the lord of the present,” who takes the material wealth of the world and churns through it in “growling machines doing his will.” Whether you take only a material view of this spiral, or a spiritual one as well, this grasping and growling seems to embody the weight of suffering we may experience and see around us. From the large-scale cruelties of government policies to the small, secluded insults one man shoves at another, something bigger and endlessly oppressive connects all these different threads. The atrocities humans do in their own name (and sometimes in God’s), and make in their own image, are a testimony to this entity.

Will all good things, and people, I used to know get swallowed up by this wave? My prayers are small and frantic, having watched the wave grow over a long period of time with no visible plateau. Now in the angry stage of grief, I have continued on doing all the things I usually do as calmly as I can, but it feels like a double life, when the reality of terrible things keeps coming back to me like a perennial nightmare (often literally).

This past Sunday, I was presented with two Psalms that seemed to carry on Rilke’s theme. One was Psalm 2, the focus of our morning sermon, and the other was Psalm 37, the source text for a sermon I had been meaning to listen to for a while (on envy). Together, they represent the journey from humankind’s powerlessness towards Christ overcoming the world.

Why do the nations rage,

And the people plot a vain thing?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

And the rulers take counsel together,

Against the Lord and against His Anointed, saying,

“Let us break Their bonds in pieces

And cast away Their cords from us.”He who sits in the heavens shall laugh;

The Lord shall hold them in derision.

Then He shall speak to them in His wrath,

And distress them in His deep displeasure:

“Yet I have set My King

On My holy hill of Zion.”

“Those who will be judged,”—so did Shusaku Endo describe them in his novel The Sea and Poison. All those hurting the innocent, profaning God and His Son in their cruelty, will someday face justice. There is reassurance in realising He holds kings and emperors in derision, and all their grand machinations are pitiful in His sight. Napoleon is gone, and Hitler is gone, and many other such despots, too, have gone to await judgment.

I have seen the wicked in great power,

And spreading himself like a native green tree.

Yet he passed away, and behold, he was no more;

Indeed I sought him, but he could not be found.

This is a hope to hold onto, but with care and self-awareness. There is nobody who hasn’t, at some time, held cruelty in their heart towards their fellow man. As I listened to the talk on envy, I remembered my own unkindness towards others. Even if such unkindness “only” manifests in a stray thought or a silent coveting, who is to say it is only a small crime?

Bitterness would numb the heart to prayer, but humility finds a way to ask God that even the old emperors of earth will turn towards repentance and reconciliation while they are still able. We share more in common with them than we would admit. And in the end, the rage of the world is inescapable—feeding on itself to no end—but only love is permanent.

Leave a comment